Since I was a child, I have looked up at the night sky and wondered: Is there anyone out there? Are we unique?

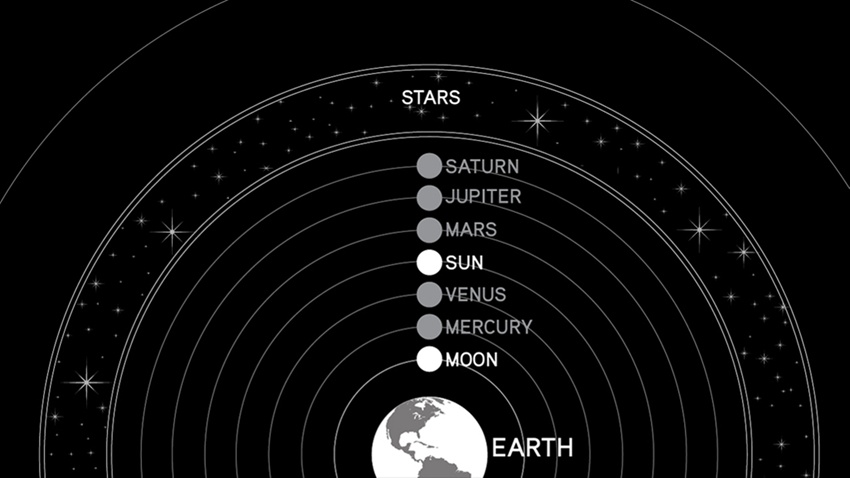

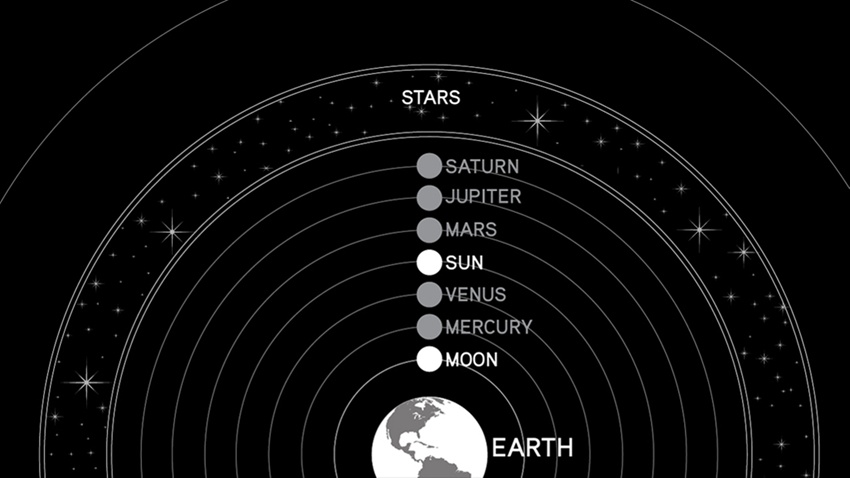

The cornerstone of Christianity is the notion that we are the center of the universe, that God created this world to be the center of all worlds. When Ptolemy published his geocentric model of the universe, the church jumped at the idea of a scientific theory to back up their "fantastical" sayings. He proposed that the stars in the universe traveled in concentric circles—with Earth in the middle—and that the universe was bounded by a background strip riddled with stars.

|

| Modern depiction of Ptolemy's model |

However, Ptolemy's geocentric model came with an inherent anomaly, the fact that some stars deviated from their predicted routes and made twirls in the sky. Nowadays, we understand that those stars are planets near us, and the swirls they make are just byproducts of relativist motion to the rotation of the and surrounding planets. Back then, to explain this bizarre phenomenon, Ptolemy introduced the idea of epicycles, that stars sometimes just makes spirals within their paths.

For a while, observations confirmed his theory.

Until one day, Copernicus came along and used a different model to explain retrograde motions explained by epicycles. By observing the path of the Sun in the sky, he manifested the heliocentric model, where the Earth and other nearby planets orbited the Sun. This way, he was able to take the ungrounded idea of epicycles out of the equation and still accurately match theory with observation.

It was not until Galileo that provided the first piece of evidence to truly support Copernicus's theory. After investigating the use of optics to magnify light, Galileo made his own telescope, powerful enough to discern the four largest moons of Jupiter (Lo, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto), which we now call the Galilean Moons. He found empirical evidence that those moons orbited around Jupiter and not around the Earth, disproving the Geocentric theory. Although his discovery was considered heresy, forcing him to recant his teachings, the Heliocentric model began gaining massive support.

Later on, the work of Newton, describing the laws of universal gravitation, and Kepler, who deduced the equations that govern planetary motion, that led to the confirmation of the Heliocentric model we know and learn today.

I always thought I loved physics because of the outlandish ideas proposed in the study of quantum mechanics. In retrospect, the moment I gazed up at the night sky might be the moment I fell in love with physics.

It's amazing to think that, hundreds of years ago in ancient Greek, someone just like me looked up at the night sky and noticed that the scattered speckles of light seemed to move ever so slightly. So he/she named them "planētēs", Greek for "wanderer".

I easily step onto extended digressions. It might just be the way my brain synthesizes information. Anyways, back to the main query at hand: are we alone?

There are arguments for both sides, but personally, I prefer to think that there must be some lifeform out there, maybe more or maybe less evolved, wondering the same question as they stare bewildered at the starry night. One scientist says it all in one quote, "The universe would be a waste if we were the only ones to enjoy it."

The origin of the universe itself is trippy, to say the least. After the initial implosion of the big bang, particles and antiparticles cancel out in mutual annihilation, releasing massive amounts of energy that are still detectable today in the form of cosmic microwave background radiation. It is by pure chance that there was one additional particle out of every billion particle-antiparticle pairs. That odd one out per billion is that makes up all the mass in the universe today.

And that all happened in the first millionth of a second since the birth of the universe.

And are we unique? Well, we've been dying to find out since September 1977, when NASA send footage of Earth on a probe out into space, hoping that one day an extraterrestrial with enough intelligence would be able to decrypt the code (which was transcoded in a hydrogen-based code, very clever) and return a message.

According to statistical models, there is a high probability that there is some form of extraterrestrial life out there. Then, where are they and why haven't they contacted us yet? Human civilization has only been around for 300,000 years, but the milky way has existed for millions. Shouldn't some alien civilization have already developed interstellar travel, or at least, communication? This is the basis for the Fermi paradox, which finds the lack of evidence paradoxical to the high probability of extraterrestrials.

But for the sake of argument, let's assume for a second that we are alone. Why then, are we alone?

The best hypothesis is a theory known as the Great Filter. The concept is that there is some catastrophe, something so great that all previous civilizations on any stars were unable to survive. This could have been the reason for the absence of other lifeforms. This could also mean that our civilization is about to face that very filter, something we couldn't dodge. This is what scientists today are worried about. Maybe it's an irreversible global warming that destroys our planets and, consequently, us. It is a dark road to go down.

There is also another possibility that the Great Filter is behind us, that the asteroid that destroyed the dinosaurs (which lived for millions of years) was the filter. Life, somehow, managed to squeeze through the cracks and burst out living again. This is an optimistic view and hopefully, this has happened.

This could only be resolved if we knew if other civilizations exist out there.

We have sent out electromagnetic waves in all frequencies in attempts to contact potential lifeforms out there. Maybe one day we'll hear back from them. Maybe we already have; we just didn't decode it yet. But I'm always hopeful, hopeful that someone or something will respond, hopeful that it will happen during my transient lifetime.

As the night grows darker, the stars, again, appear against a solid black backdrop. After so many years, I'm still fascinated by the galaxy. Every night, I'll be stargazing, and, like my 8-year-old self, I'll continue to wonder what could possibly be out there.