Recently, I've been attempting to reconcile two disparate situations. How am I able to do certain things very well despite not having much prior experience, and yet certain other things come utterly horrendously, perhaps even with a little more experience?

For instance, I was able to establish a networking association, starting from just me, myself, and growing it into a full-fledged, multi-level organization, with hundreds of people attending each event from across five university campuses and over 20 high-profile professors, including deans, speaking at these events. I was also able to host an entire conference—a TEDx conference—with 10 high-profile speakers, a full-fledged auditorium, getting approval, getting validation, getting people in line to make it happen. This could and should have been the work of a group of people over the span of three months, but it was all done mostly by just one person, and that is myself.

Both of these I had minimal experience in beforehand, yet I was able to learn on the job and get shit done. Make it happen.

Yet when it comes to research—something I've had some exposure to in the past, and something where I have a reasonably good idea of the process—I am failing horrendously to achieve more than the minimal 20%. I can barely push anything out at all. Why is that?

Now, you could say, well, I once argued that the methodology wasn't correct. Clearly not. I didn’t learn things the “right” way. I should have started from the fundamentals and then moved forward, and no one told me that. But really, I didn’t know how to do either of the other two either, yet I sought out the help I needed and learned on the job. So clearly, that’s not the reason.

Maybe it's a skill issue. I just can’t get things done. I’m just bad at focusing and executing. Well, not really. Okay, yeah, a little bit, I agree—but not particularly. I was able to get many things done in the past. I was able to force myself to do a lot of things, and even though they were all very taxing on the mind, much of the stuff I do is mentally demanding, yet I was still able to do them persistently over a year and think about them constantly.

So what is the difference? Why am I able to seemingly do certain things so well despite having no experience, and yet other things so poorly despite having a little experience?

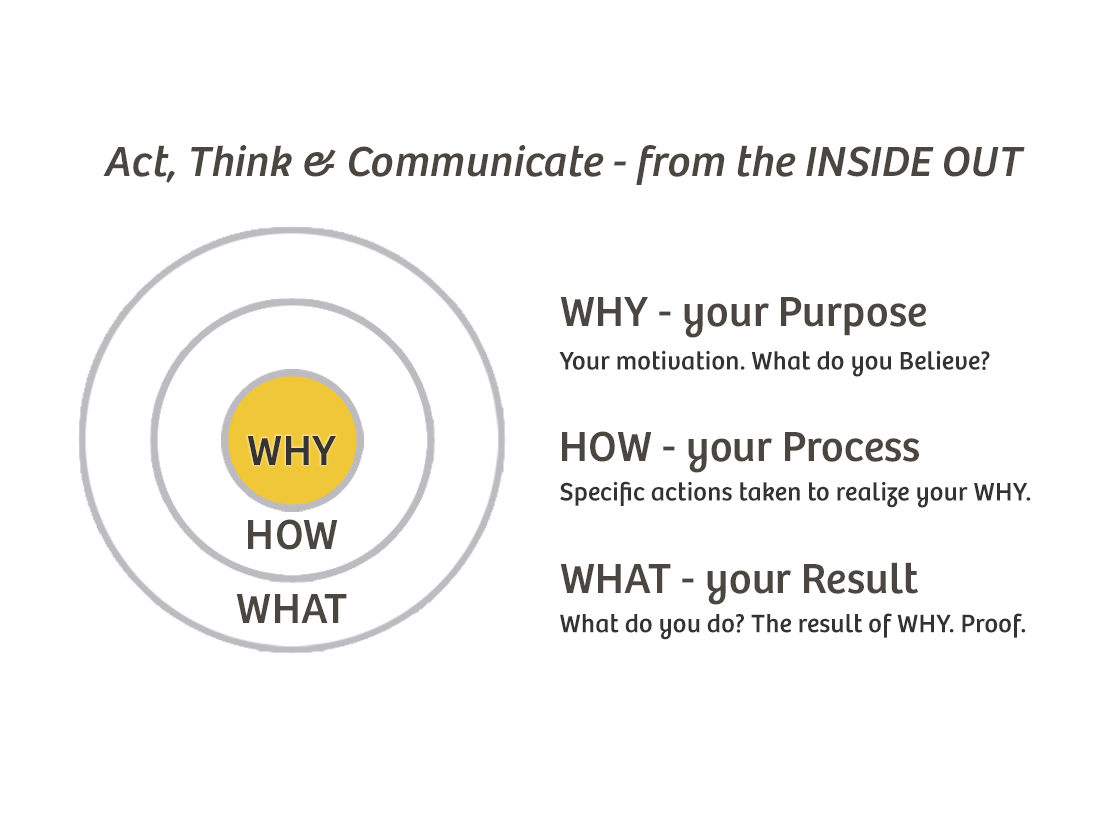

I think I figured it out. After seeing the golden circle theory, I think I figured it out.

When it comes to running a networking association or bringing about a TEDx event, the reason I was able to accomplish those was because I innately believed they were meaningful. I saw the meaning. I saw the meaning of connecting people and creating such a large network that would help each other. I saw the meaning of embracing a globally renowned conference to enable the school to share its perspectives. I saw the meaning in doing it because I believed in giving back to the school and making it better because of me.

But with research, the reason I did it in the first place was because I wanted external validation. I wanted the result of having a diploma, of being called a doctor, of having a PhD. That was really it. And that’s a very weak-ass motivation. That’s coming from the outside in.

Maybe having it would give me a higher salary. Yet again, it wasn’t intrinsic to what I believed.

For a while, I was incredibly stressed because some of the external “whats” got to me—pride, people not treating me seriously, or maybe not being able to find a good job in the future. Both of these got to me a little, yet again, they weren’t intrinsic. I didn’t intrinsically see meaning in those in terms of spending my life on those goals. And thus, I couldn’t see why I would want to do any of those things.

And as life would have it, when I do see meaning in doing something, I do it very well, as proven by my previous events.

It’s simply a difference in mentality. It’s healthier, it’s more sustainable, and it makes me do both the how and the what. In the end, you achieve the what—but there are two ways of getting there.

One is from the inside out: starting from a purpose that naturally, organically motivates your emotional system. It triggers your emotional system to be emotionally invested, and that then propels your higher-order thinking to figure out the how and the what.

The other way around is to be completely rational—which we are not, as we’ve proven. Humans, before any title, are just humans with a lot of fucking emotions. To be completely rational, or to trigger a fear response for the result—to think only about outcomes, or to scare yourself with consequences if you fail—is not healthy.

Thinking of a result and then trying to backfill the why isn’t sustainable. People don’t find joy or meaning that way.

Triggering a fear response, on the other hand—“you’re going to fail, you’re going to die, you’re going to be disrespected”—maybe that can be a why, but it’s a terrible substitute why. It’s like the Iron Man core that’s poisoning him. Yes, it gets people moving. Absolutely, it gets people moving. People respond to fear very effectively—but only in the short term.

Then people burn out. They become disenchanted, tired, lifeless.

The problem is that fear responses limit higher-order thinking. They overwhelm it. In the long run, they narrow higher-order thinking into fight-or-flight mode. You choose whatever lets you survive or escape the fear the fastest. That narrows options down to less creativity, more brute-force or even unhinged solutions.

That isn’t sustainable, and it doesn’t scale.

So there are two ways of motivating yourself. If you go from the outside in—“we need the result, therefore we need the how”—you lose meaning. People don’t understand why they’re doing it at all.

If you then add fear to force a why, it works briefly, but only for people with weak character structures, and it produces shallow, uninteresting solutions because they’re just trying to escape.

Now, a lot of people say, “There’s no meaning in a lot of things. You don’t feel the why in the beginning. You don’t find the fun.”

First of all, it doesn’t have to be fun. It just needs meaning—a named motivation that triggers an emotional response. You need to trigger something you genuinely care about. That’s the key.

Second, people say, “Once you do things, you’ll find meaning.” Maybe. But it doesn’t always happen.

Many times, the meaning is just survival, or pleasing a parent, or believing in an advisor or supervisor. That’s why you see prodigies who achieve everything, get all the validation, yet live unhappy lives, burn out early, or want to escape. There’s no inherent meaning in what they do—it contradicts how they view the world and what they value.

You must begin from values. If values align, and you frame things so that meaning sits at the bottom of everything, motivation becomes organic. People think better, do better, and it’s far more sustainable and healthy.

That’s how I solved this conundrum.

--- Interjection ---

There is one thing, though. Before I found meaning, I really should have been actively searching—very, very actively searching—trying things and asking around. Instead, I was just filling up my time, and my need for meaning, and the lack of it, with very low-level entertainment that numbed my senses. Modern-day drugs, essentially.

That’s something I need to get off of, because it dulls your senses entirely. It’s basically opium for the new age, and it actively hinders you from even going to find your meaning in the first place. Maybe without it, I would've reach many more revelations much faster.

--- End of Interjection ---

So the practical question is: what about research now?

I see the meaning now. I finally see the meaning of doing research.

Research today is different. Fundamental research translates incredibly easily now. I’m closer to application. My field affects literally every industry on the planet. By doing research, I’m contributing a piece of infrastructure that will hold up the world in five to ten years.

That is meaningful.

That is contributing to the world, which is what I’ve always wanted to do with my life. And that gives me deep joy.

To truly contribute something—something where people can say, look, Felix is the guy who did it.

Now, both ways do eventually get things done, and perhaps eventually, successful people come to similar conclusions about life, no matter which way they were exposed to initially, that you need both ends, and that motivation from the inside-out is more sustainable while the outside in allows more resilience in the darkest hour.

But, from the perspective of a developing country, outside in works great at getting more people to do some work.

From the perspective of the next level of humanity, it is inside-out that gets you people that peak, much much higher, and seemingly superhuman to the rest.

—

This article, and most on this site, are written in one sitting, with minimal edits. So, please forgive the occasional grammatical mistakes—it takes a certain spontaneity to transcribe genuine, unfiltered thoughts.